Part I: an Introduction

Why Decentralize Finance?

In one word: trust. Or, ironically, you could also say trustless. Allow me to explain. For the same reason that Bitcoin is successful without a centralizing third-party─namely that you can transact with a perfect stranger in a foreign country by trusting the protocol and you don’t need to trust the stranger─the cascade of financial products that can be built upon digital money is an ideal fit for blockchains.

Anything you can do at a bank, or an investment bank, or a hedge fund, or a stock exchange can be built in code and run on a blockchain. There are number of more practical reasons why someone would be interested in decentralised finace such as higher yields than found in more standard financial products, lower fees, transparency, easier access to foreign markets, more fine grained control (you can program it), etcetera.

I could go on, but lets detail some of these innovations happening in defi-land.

Stablecoins

The primary advantage to having a fiat currency on a blockchain is to map value from your bank-and-mortar world to the crypto-digital world without being exposed to the price volatility of tokens. I can exchange $1 dollar for 1 crypto-token, say, USD-Coin (USDC) and be assured that 1:1 mapping will hold. For business operations, valuations, projections, and so on this is crucial. The secondary advantages come from all the benifits of having a cryto-native platform such as low fees, fast settlements, auditability, programmability, and censorship resistance.

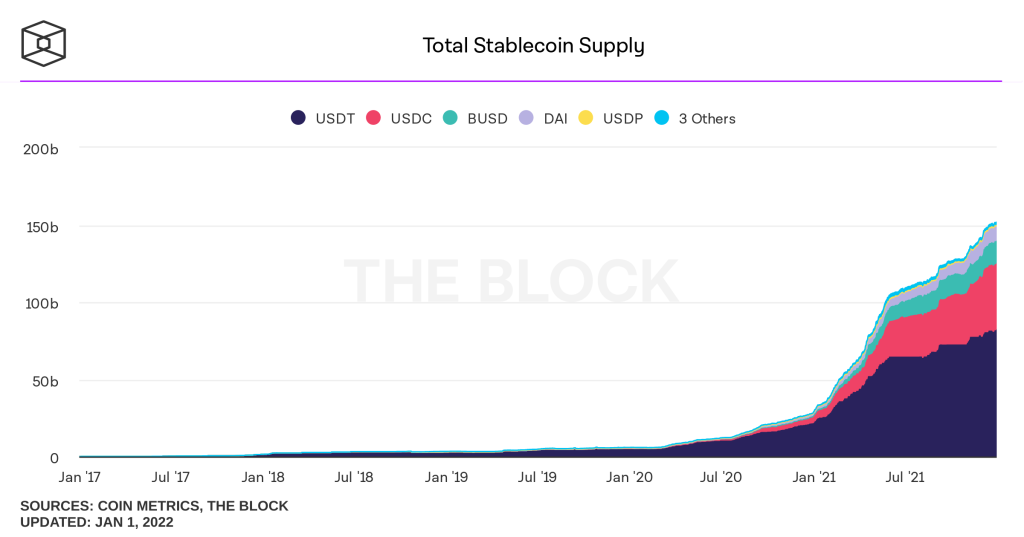

It is hard to ignore the growth and popularity of stablecoins when looking at the total value. This chart from TheBlock is showing growth in stablecoins over the past four years. In 2021 the total value of stablecoins rose from ~$28B to $150B USD. DeFi has been largely responsible for this increased demand for a variety of stablecoins as they are useful for liquidity provision, farming, lending/borrowing, or short term settlement.

The top five by supply are Tether USDT, USD-Coin by Circle USDC, Binance USD BUSD, and Dai DAI. Tether, USDC, and Binance’s USD are issued privately, whereas DAI maintains a US dollar peg by holding crypto assets in its treasury managed by a Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO). Here is a partial listing of stablecoins, the currency they are pegged to, the collateral backing the peg, and the blockchains where they can be found.

und.

| Stablecoin | Currency Peg | Backing | Blockchains |

|---|---|---|---|

USDT | USD | mix of assets | Ethereum, Algorand, Tron, BSC, Solana, Fantom, etc. |

USDC | USD | USD | Bitcoin (Liquid), Ethereum, Algorand, BSC, Solana, Stellar, etc. |

AUDT | AUD | AUD | Ethereum |

NZDS | NZD | NZD | Ethereum (still in beta as of Jan. 2021) |

XSGD | SGD | SGD | Ethereum, Zilliqa |

EURS | EUR | EUR | Ethereum, Polygon, Algorand |

DAI | USD | crypto collateral | Ethereum, Polygon, BSC, Fantom, Gnosis |

PAXG – Paxos Gold | 1 oz of gold | physical gold | Ethereum |

There are other varieties of stablecoins, including ones that have no collateral backing and are controlled algorithmically. More on these in Part II.

Decentralised Exchanges (DEXs)

Most crypto (and all stock) exchanges are centralized and use an order book to match trades. Called the central limit order book (CLOB) model, this works very well for a corporate structure such as the NZX (New Zealand Stock Exchange) that can have complete control over their servers and centrally manage events. The order book is a list of all the open buy/bid and sell/ask orders for a stock. Its the job of the software matching engine to aggregate and fill as many orders as possible at the market price. This type of model does not scale to a blockchain because of amount of activity that would need to be written to the chain; all bids & asks for example, and the latency when updating the actual transactions, especially for time sensitive updates like access to price feeds during liquidations.

The decentralised way to run an exchange requires three things: a swap method for users to exchange assets, a pool of each of the assets to draw from, and a method to determine and set the price (make the market).

In order to swap one asset to another a few prerequisites must be in place. There needs to be enough of the asset available you want to buy, and there needs to be a buyer for the asset you want to sell, and lastly, a fair price is agreed upon by both buyer and seller. Swaps here are directly between two assets at one time, e.g. ETH <--> USDT, although multiple hops or paths can be routed by the protocol.

The assets are drawn from existing pools of the same asset pairings, e.g. ETH-USDT, or DAI-USDC. (Keep in mind there is no broker behind the scenes sourcing the stock or using their trading account to buy and sell. For common, high-volume shares the broker doesn’t go to the trouble of finding a buyer/seller for every transaction, they will do this on their own account and settle later.) If you want to swap some DAI for ETH you need a separate pool just for this pairing. Where does the pool come from given that there is no exchange?

Here we have a problem in getting a DEX up and running: you need a pool of assets before users can swap between them, and you need users to come and swap assets. But why would someone deposit their assets to create a pool? Well, they are incentivised by the protocol; paid for their efforts by earning a share of the transaction fees, or extra tokens, or both. Ideally this is self-reinforcing. If the fees are profitable, people will add liquidity which attracts users and generates more fees, ad infinitium.

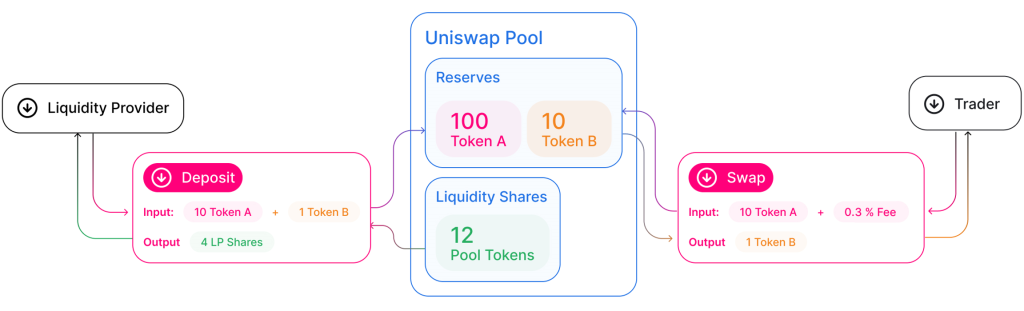

Creating a pool (from the Uniswap docs) shows the Deposit function taking 10 of A and 1 of B to pair in the ratio 10:1 into the pool. The provider receives 4 LP share tokens that might look like A-B-LP. The number of LP tokens received will be a proportional representation of the pool. On the right a trader accesses the reserve pool to swap A for B.

To create a pool I just need to deposit two assets into the protocol’s smart contract. Its in my best interest to add equivallent values of each asset; in the example above Token B is ten times the price of Token A and so the ratio of A:B I want to deposit is 10:1. At this point I am issued an LP (liquidity provider) token representing the combined assets, which might look like: USDC-ETH-LP-v2, meaning I now have a proportional amount of the USDC-ETH pool as an LP for version 2. This is the receipt proving my commitment and I must hold onto this USDC-ETH-LP-v2 token to be able to withdraw liquidity and claim any rewards. Note here that because I hold a single token (not two separate ones) I am exposed to second-degree market effects as the independent fluctuation in price of either token away from the ratio (e.g. 10:1) affects my position. More on this later in impermanent loss.

Automated Market Makers (AMMs)

The third piece here is the automated market maker that works just as described; it algorithmically ensures that every bid can be matched with an ask, thus making a market for any token pairing. With a large enough pool of liquidity the price will remain stable and match the market. However, if the pool runs thin it will be difficult to place a large order or to maintain the quoted price (called slippage). This imbalance won’t last long as it provides a profitable opportunity for some arbitrageur to ‘rebalance’ the pool and get some tokens at a discount.

This AMM model has many benefits that fall in line with a decentralised ethos:

- users can create their own trading pair; very useful for smaller or new assets or pairings

- users self-custody their assets & vice versa -> the protocol isn’t directly responsible for user’s capital

- accessibility: the crypto markets are global and thus run 24/7, so a user only need access to the protocol (via the internet) to trade in any market at any time!

A few downsides:

- slippage – how the price moves for orders of a large fraction of the total pool liquidity

- impermanent loss due to the market value of token pairings becoming unbalanced (more later)

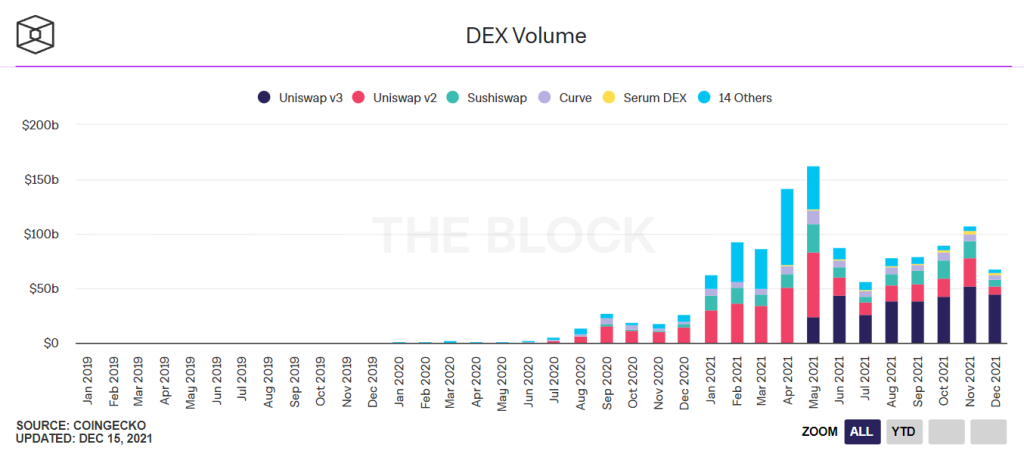

Uniswap is the leader in terms of activity for decentralized exchanges. The chart from TheBlock shows that they have maintained over 50% of the market for the past few years.

There are two versions of Uniswap: v2 and v3. This is a quirk of decentralized blockchain developement. Once the app code, in this case the Uniswap contract, is deployed on a blockchain, its effectively set and cannot be edited, updated, or have bugs fixed. This immutability is a key feature of blockchains and dapps, however, it means that for a project to have a new release they have to deploy another contract which introduces migratory challenges (and significant cost). Also, Uniswap v3 has many new features such as concentrated liquidity, and limit-like orders, that increase efficiency for traders.

Oracles: Where do the prices come from?

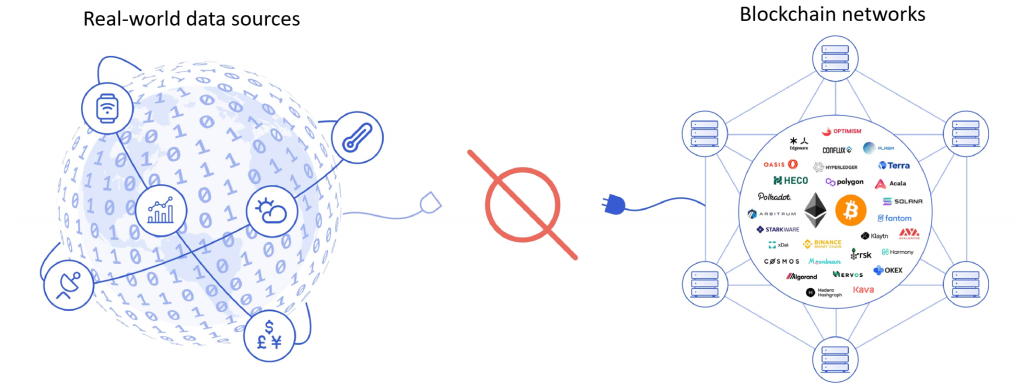

An oracle is a source of truth that connects the outside world to blockchainland. Smart contracts cannot know in advance the price of an asset and so must query some service that maintains the price feed. This information can then be used to update the state. For example, in a prediction market there may be a bet for the next winner of the World Cup with all funds locked in a contract until the final. At this point the contract needs to be aware of who won before distributing the winnings. Another example could be weather reports on flooding to settle an insurance contract. Oracle feeds help getting real-world data into the blockchain.

If a blockchain used a regular API to get information there would be differences based on the time it was sent. All nodes in the network need to verify the data so they must use an absolute source for truth, including going back and verifying old transactions, so any pricing or oracle data needs to written into a block. Uniswap has developed a method to store price data on-chain which mitigates some of the issues to do with block latency and price volatility by using time-weighted average prices (TWAPs). Chainlink is a blockchain oracle service provider and they have developed a network of decentralized off-chain providers that cryptographically sign messages attesting to information which is then aggregated before being written to the blockchain.

To avoid an issue where a service is not available when needed or perhaps a feed has been manipulated it can be designed to use multiple oracles by, for example, combining Uniswap and Chainlink data, adding your own weighting function, and publishing the result. Others use the Chainlink infrastructure to create their own oracles.

Liquidity Mining & Yield Farming (? ? ? ?)

In the beginning when a DeFi project is just getting started they can also entice users with high reward rates in the form of a native token. This process of committing assets to pools to earn rewards is called liquidity mining. By adding liquidity you take a risk of impermanent loss but can reap rewards from transaction fees.

Farming took off in June of 2020 when Compound decided to transfer control of their DeFi borrowing & lending product to its users by depositing tokens in a smart contract that would vest automatically over the next four years to the users in proportion to their activity. The resulting COMP governance tokens can be used to vote on future protocol decisions or traded on the open market. It was very popular.

This is where the DeFi game theory starts to get interesting. High early rates create a race-to-the-bottom scenario where early adopters and high rollers earn a lot of new tokens, then the rewards decrease as the tokens are vested, the player wants to lock in some profits and so withdraws their liquidity, claims their rewards tokens and sells them on the open market. If enough people do this the token price will fall and users wont’ be as attracted to the swap anymore. The high-roller that just sold their new tokens now is on the hunt for the next pool to mine for liquidity.

These terms are used interchangeably, but we can pencil some lines around them.

Farming refers to the idea that you can take a token and plant it to reap rewards. Rather than holding a token in your wallet until you use it or waiting for appreciation as an investment you can send that token to a farm or a pool and earn yield by doing so.

For example, if you deposit ETH into Curve you are issued LP tokens and earn yield from fees. Next, my dear investor, that LP token doesn’t need sit idly in your wallet, it can go out into the world and start working for you. How you say ?? Well fren, deposit the LP token into Curve’s staking pool and earn their native token CRV while still earning those fees ?.

This is an example of liquid staking where your original tokens are locked in a vault, but the receipt, the LP tokens, can be used in other settings. Staking comes from the consensus mechanism of proof-of-stake that secures the blockchain through validators that have locked up the native token as collateral so that they won’t allow nefarious transactions or activity. A number of third-party services will offer interest rates on crypto deposits in the range of 1-10%. These rates are generated by the service staking the token and distributing network rewards back to its customers. In terms of the DeFi spectrum, staking is low-risk, low(ish)-reward territory.

Mining is more of a non-renewable operation; the larger the stake your tokens have the more rewards they earn. To continue the analogy the governance token that is rewarded may have a fixed upper limit; once all the tokens are mined no more are issued (or the rate of issuance changes).

DeFi’s first iteration (1.0) consists of liquidity provision of two assets paired, or staked, in a pool. Recently there has been a move to single-sided staking so that you can still earn yield but are protected from impernanent loss.

The biggest known risk to provisioning liquidity is called impermanent loss which means that the value of the token pair you have committed to a pool becomes unbalanced when comparing present value to the price at the time you deposited. As one of the tokens goes up or down in value (due to external factors) the ratio of the token pair is automatically adjusted to maintain a fixed level of liquidity. The loss becomes permanent when you withdraw liquidity from the pool and are paid out a different number of tokens than you started with. See Pintail’s medium post for a detailed example.

For this reason it is safer (lower risk) to add liquidity on pairs that maintain a narrow price range such as stablecoins or wrapped tokens that track their unwrapped version closely. Despite the volatility in ETH, AMMs such as Uniswap and Sushiswap have been tremendously successful because LPs can also profit from pool swap fees. If the token pairing is very popular transaction fees can outweigh impermanent loss. Uniswap charges a fixed 0.3% per transaction and LPs are entitled to a cut of those fees proportional to their liqudity.

The long game here for a product is to gain users, lock up more liquidity, generate fees to attract more users and so on to reach a critical mass (although few things in DeFi are critical-mass rock-solid). A few strategies that teams are using include deploying contracts on as many blockchains as they can manage, e.g. Sushiswap is available on over 14 different chains. Another strategy is to upgrade the protocol to be optimised for Layer 2 deployment, as Uniswap did with v3 for Optimism and Arbitrum.

These strategies need to be employed in the hostile world of open-source smart contracts. There are no patents or industry secrets. If a new product is popular and attracts a lot of users and their cryptocurrency it is likely to be forked and copied quickly.

Worth considering here when talking about project sustainability is that something like Uniswap is a contract that once deployed to a blockchain is immutable. This means its expensive and difficult to upgrade. So, even if users migrate away from a protocol, it will still live (and can be active) on the blockchain for a long time without the ongoing maintenance and staff that a business requires.

In Summary

If we can have stable dollars on a blockchain mirroring the value of a real dollar, and we can have completely fabricated digital assets, all adhering to the principles of digital scarcity through cryptography, then there is a vast spectrum of possiblity opening up. We are presently at the very dawn of this financial revolution and there is sure to be much innovation and heartbreak ahead.

Just like Satoshi solving the double-spend problem can’t be unsolved, once people caught on to the benefit of financial wizardry in the form of decentralised finance, their only limits are creativity in code. And perhaps regulation. But that is a topic for another post on another day.

I hope this has been a reasonable introduction to the world of DeFi and some of the foundational building blocks. I found I had to cut many topics to prevent bloat, pushing many of them to Part II, so please have a look.

Further Reading – the very short list

- History of DeFi by Finematics

- How does the AMM actually make the market? AMMs &

ImpermanentDivergent Loss by Pintail

About the Author

Jeff is a Senior Lecturer in Blockchain & Cryptocurrencies at AUT and an Executive Council member of BlockchainNZ. He can be found tweeting about crypto at @japple.