Introduction

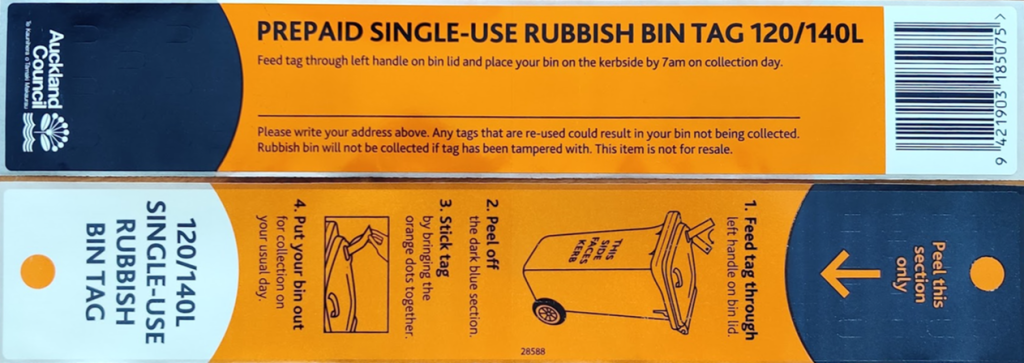

Why would tokens need an introduction you ask? Lets start with an example. Here in West Auckland we need to put tags on our rubbish and recycling bins before they will be collected and emptied by the waste disposal folks. Not just any tags though. The nice plastic stickers have to be the ones specifically appointed by the council. You can get them at the grocery store or library, but you will have to pay. Presently $3.80 for a standard 120 litre bin. ($4.25 if you’re on the North Shore. Fancypants.)

The tag is a token. Each one is interchangeable with another one of the same colour. Each one has an underlying value determined by the issue price set by the council and enforced by the difficulty in conterfeiting. The tag can be transferred to someone else whereby possession indicates ownership. And each tag has utility, in this case a weekly empyting of your bin. In an extreme scenario you could even imagine a tag market emerging where those close to the tag-printer skim off the top and cut their neighbours in on a discount, benefiting both parties financially. Eventually the council will have to raise tag prices to cover the loss and thus hit the average every-tagger in their weekly budget. This embezzlement has now inflated the price of a tag and distorted their value (the rubbish trucks still only collect 1 bin per tag). The Council rubbish tag racket is a hidden tax that disproportionately affects the lower socioeconomic class. Thankfully this is just a hypothetical scenario.

Back to the tag being a token. The digital representation has many of the same properties: it is fungible (interchangeable), scarce (can’t be copied), valuable (someone would pay for it), transferrable (not tied to someone’s identity), and has utility (otherwise why do I need it?). It is also secure (can’t be stolen). We have just described many of the properties of money itself, and this may be why a distinction between cryptocurrencies, utility tokens, securities, and collectibles can be fuzzy and subjective. Without getting into the weeds, a $20 note is a physical token, but $20 in your bank account app is not a digital token─its just a promise stored in the bank’s database.

Are Coins Tokens?

If you have some bitcoin or ether, yes, these are digital tokens because they are fungible, secure, scarce, transferrable, and have monetary value and utility. (Bitcoin’s utility is widely considered to be a store-of-value.) Its confusing at first but there is a difference between value and utility. In Bitcoin’s case the utility is value. For Ethereum there is broader application, e.g., using ether to purchase an NFT or invest in a new project or pay gas fees. Many tokens claim some form of utility and let value be determined by a market. It is a regulatory grey area when it comes to classifying tokens as securities or otherwise, and has implications for taxation and reporting.

Non-Fungible

Currency tokens (and cash) are interchangeable, or fungible, because it doesn’t matter what specific token you have, everyone agrees on the same value. If people were willing to pay a premium for specific tokens or characteristics, then the overall utility of the medium as money begins to fall apart. This is the problem with barter; there is far too much subjective difference in value between objects for people to easily exchange goods directly.

Think of paintings in a gallery. All the paintings are similar in many respects─composed of paint, multicolour, framed canvas, 2-dimensional, etc.─however, each painting is obviously unique with value determined by many external factors. Non-fungible tokens, where each unit is unique, are designed for this purpose. In a digital manner they implement security and scarcity. Value and use are subjective like gallery paintings, but these now inherit the open, permissionless, censorship-resistant properties of the blockchain.

NFTs aren’t just for collectibles, art, and profile pictures. Any document or data structure that can be digitised can be represented as an NFT: music, certificates, degrees, licenses, passes, patents, title deeds, concert tickets, contracts, voting rights, et-cetera.

Token Standards (Ethereum)

Over time standards have emerged that assist developers with creating new projects, building functionality, and interacting with other tokens, contracts, and chains. Some of the main standards that have been developed for Ethereum are:

ERC-20

The first use case of Ethereum was generating new coins. These projects often launched with fundraising efforts called ICOs (initial coin offerings) that promised buyers a certain allocation of new tokens. All these tokens live inside (or on) the Ethereum blockchain but are separate from ether. Think of tokens as carriages that run on the rails of Ethereum and the whole train is powered by ether. The Ethereum Request for Comments #20 is the standard that defines how to make a fungible token that is compatible with Ethereum itself. Because its an open network anyone is free to make their own token and launch it on Ethereum1. The contract will live forever on the blockchain and handle functions like transfers, account balances, token creation and destruction. These tokens can be divided into as small as eighteen decimal places (0.000 000 000 000 000 001) to allow for very small and fractional payments.

Examples of the ERC-20 standard include the following tokens (among many):

DAIthe decentralized algorithmic stablecoin,LINKthe decentralized oracle network, andwBTCwrapped bitcoin.

ERC-721

ERC-721 is a standard that includes an integer variable called tokenID that must be unique. From the EIP: “In general, all houses are distinct and no two kittens are alike. NFTs are distinguishable and you must track the ownership of each one separately.” Any tokens deployed with this standard cannot be subdivided, and ownership is wholly transferred.

Examples of the ERC-721 standard include:

- CryptoKitties collectibles and game,

- Ethereum Name Service domain registrar, and

- the Bored Ape Yacht Club collectibles and club membership.

ERC-1155

Further to the previous two standards, the 1155 standard merges both fungible and non-fungible into a new standard that extends functionality. Called a Multi-token standard it can batch transfer groups of items, for example, if your game character kills another it can transfer the plundered items to the winner in a single transaction. It also improves efficiency with a focus on game design where a large number of transfers could be required and it would be cumbersome for the user to stop gameplay to interact with a smart contract and pay associated gas fees.

Examples of the ERC-1155 standard include:

- OpenSea the NFT marketplace,

- Skyweaver the game, and

- The Sandbox metaverse platform.

Non-Ethereum Token Standards

Ethereum may be the original smart contract platform, but there are plenty of younger ones vying for your tokens. Here I’ve listed some of the main smart contract platforms and their associated token standards. EVM compatibiliy refers to the Ethereum virtual machine which handles the processing of smart contracts. If compatible, the chain can understand contracts made for Ethereum which can help with bootstrapping users and projects that already exist there.

| Blockchain | Native Token | EVM Compatible? | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethereum | ETH | ✔️ | ETH is the native currency; ERC-20 tokens run on top and are processed by the EVM. |

| Avalanche | AVAX | ✔️ | Avalanche has a ‘X-chain’ for native assets but also a ‘C-chain’ designed to be compatible with Ethereum Contracts. |

| Fantom | FTM | ✔️ | The FTM token exists on Ethereum, but is the native asset of the Fantom ecosystem and can be bridged between the two. |

| Polkadot | DOT | ✔️ | Although compatible with the EVM, this is not the main functionality. DOT is a new standard of the Polkadot ecosystem. |

| Solana | SOL | ❎ | Solana has built-in support for creating new tokens; EVM compatibility is in progress. |

| Tezos | XTZ | ❎ | Tezos has its own standards; FA2 is a unified token contract interface. |

| Cosmos | ATOM | ❎ | The ATOM token can be found on Ethereum and Binance Smart Chain, but is the native asset of the Cosmos ecosystem. EVM compatibility is in progress. |

a Token’s Lifecycle

Minting ? Wrapping ? Bridging ? Burning

Many things can happen to our cryptographic tokens during their life span. To begin with: where do tokens come from?

Minting

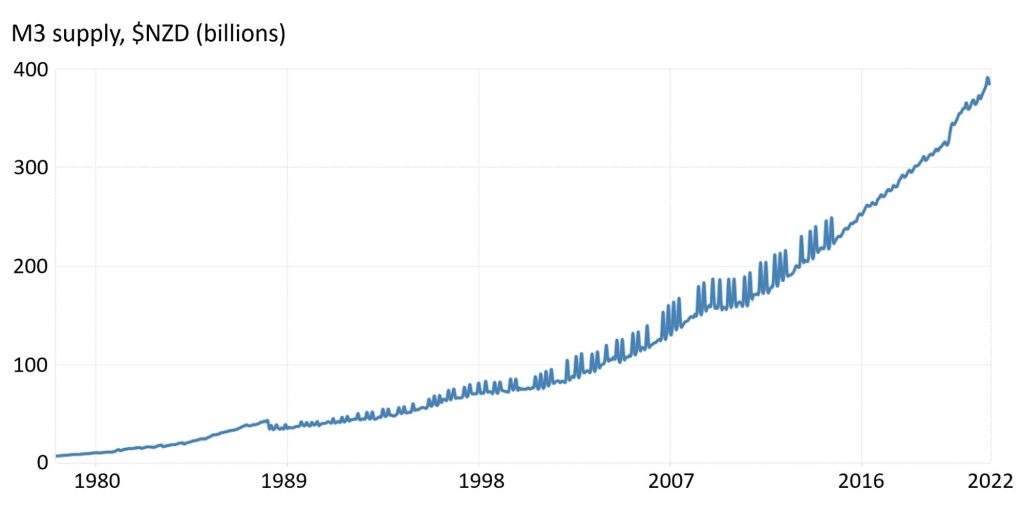

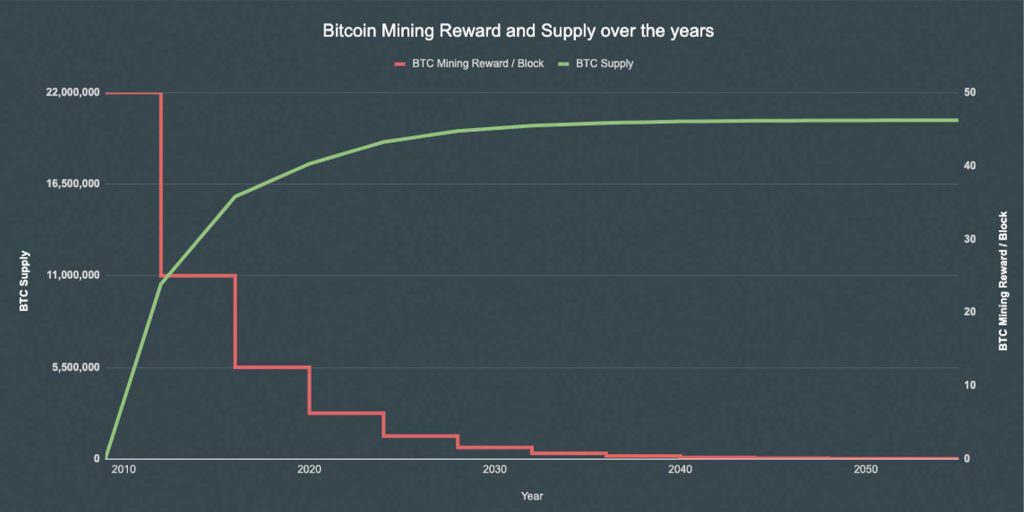

Minting tokens refers to the same process of creating tradeable items of value as coins being minted as new currency. Just as with coins, it seems best to increase token supply slowly, or at least according to a set plan. All of the New Zealand dollars weren’t created at once, rather they are minted over time as the Reserve Bank seeks to increase the monetary supply. A key difference with the minting of cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin is that they adhere to a fixed schedule, set in advance, written into the code. For example, new bitcoins are created in the coinbase transaction of every block, presently 6.25 BTC every ten minutes.

Compare the minting of New Zealand dollars to new bitcoin. Bitcoin’s chart goes well into the future as the supply schedule is fixed in code. Click for larger version.

A slow and steady issuance has its benefits such as knowing in advance how many will ever be minted. If all the tokens were created at inception there would be a distribution problem: the creator(s) would have the total supply and have to incentivise newcomers. Tokenomics is the central-planning activity of deciding who gets how many tokens and at what intervals. This is a hard problem because it involves human nature. For example: How much is too much to reserve for the creators? (called a pre-mine) Developers? VCs? Is the supply infationary or deflationary? Can the details be changed in the future?

The popularity of NFTs has brought minting into common usage. NFTs are usually created one at a time, such that when the contract is called it spawns a new token in the set which is then sent to the buyer.

Wrapping

Next, our token may want to venture out beyond its home chain and explore some of the broader ecosystem. Taking a bitcoin as an example, this token is only built to be transferred between users of the Bitcoin network. What if our intrepid bitcoin wanted to participate in some yield farming on the Ethereum blockchain? One method to do this would be for someone to act as a escrow service and hold your bitcoin (on the Bitcoin blockchain) while releaseing a new bitcoin-ish token (on the Ethereum blockchain). This is where wrapping comes in. The new tokenized version, wrapped bitcoin, or wBTC, can be used in Ethereum wallets and apps while tracking the value of bitcoin 1:1. Ether itself can be wrapped to travel to other chains where it may be seen as wETH.

Bridging

Transferring tokens from one blockchain to another requires a bridge because there is no native compatibility between blockchains. In a multi-blockchain world interoperability is a necessity to transfer value from one chain to another2. An analogy on bridging tokens comes traditional finance. To send money overseas a third party needs to buy the first currency and then sell you the second currency. The forex broker or bank is fine with taking this position because they can resell the excess currency while earning a fee. This parallel isn’t entirely accurate because the bank is not minting new currency to sell you, rather they are using their inventory. The blockchain case can involve creating new tokens or purchasing pre-existing sythetic ones..

The process to bridge tokens from Bitcoin to Ethereum, using wrapped bitcoin as an example:

- send

BTCto a trusted third party custodial service; wrapped bitcoin uses BitGo BTCis locked up and held by BitGo; its visible, but not available on the bitcoin blockchain- BitGo mints new tokens called wrapped bitcoins,

wBTC, in an ERC-20 contract, to be used on Ethereum. The wrapped version must track the price of the original token. Value transfer in this case is 1:1, and any deviation would be an opportunity for arbitrage. - the custodian sends

wBTCto the user and can now be traded as an ERC-20 token.

To bridge back, or redeem, from Ethereum to Bitcoin:

- send

wBTCto BitGo’s contract wBTCis now taken out of circulation by burning- original

BTCis unlocked and - sent to the user on the bitcoin blockchain

For minting and burning wrapped bitcoin through the steps above the third party collects KYC information and so this process isn’t entirely decentralized. For retail users that don’t need to mint/burn and just want to use wBTC they can still use a decentralized exchange like SushiSwap or Uniswap to get the token. According to DeFi Llama there is over $13B bitcoin that has been bridged to other chains, mostly Ethereum.

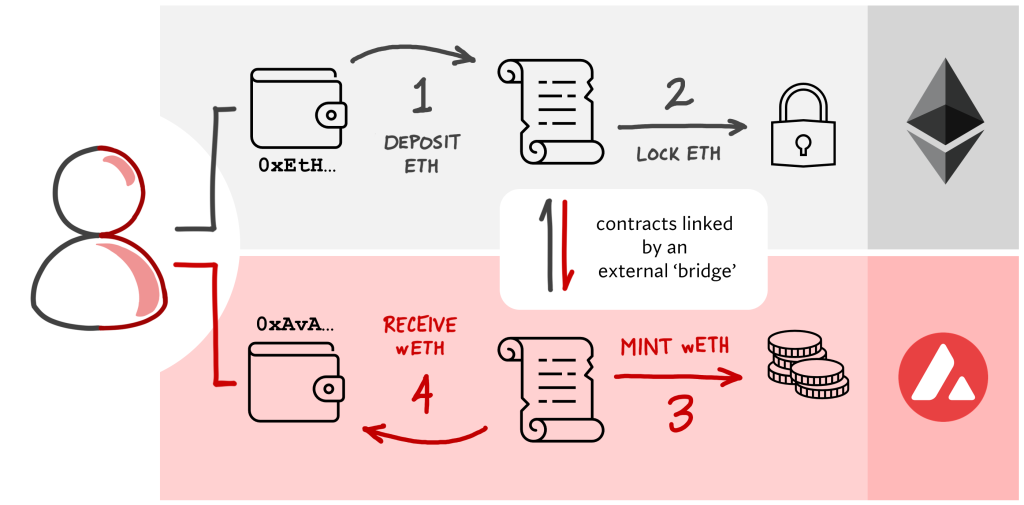

The general bridging process is shown in the diagram below, this time using Ethereum as the native blockchain and Avalanche as the destination. First the ETH is deposited into the bridging contract, it is locked, and the bridge is activated to mint new wETH tokens on Avalanche, which are then sent to the destination wallet. Redemption happens in reverse except step 3 is replaced with a burn, and step 2 is an unlock.

Bridging isn’t just for bitcoin and ether. The Multichain service has over 600 bridged assets across most major blockchains. They also have a router for multi-chain bridging and support for NFTs. Multichain’s protocol relies on a network of nodes and results in a decentralised trustless service through some clever cryptography called Secure Multi-Party Computation.

Burning

Burning tokens is a provable way to remove them from circulation and the overall supply. This is necessary,as we saw above, in bridging operations to prevent supply inflation or theft. Protocols may also want to burn their tokens according to scheduled supply changes or upgrades. Part of the Ethereum network’s transition to proof-of-stake involved an upgrade in July 2021 that changed the fee distribution policy for miners. After the London hardfork, miner’s fees were split into two groups with a base fee being burned and a priority fee going to the miner. This has effectively changed the supply of ether from inflationary to defationary.

Practically speaking, tokens are burned by being sent to an unspendable address. This provides the verification that they can no longer be used. For Ethereum this means the recipient address has neither a private key nor a contract capable of accepting ether. You may have seen some burn addresses:

| Ethereum address | note |

|---|---|

0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000 | the zero address; this is a default used for contract creation |

0x000000000000000000000000000000000000dEaD | note the “dead” in hex at the end |

0xdEAD000000000000000042069420694206942069 | not technically unspendable but highly unlikely this address is ever generated |

Sending any tokens, either accidentally or on purpose, to these addresses will be interpreted as a burn and result in a loss of funds.

A Cautionary Note

Sending tokens to any address that you do not control or have the private keys to requires diligence in checking the destination, both to ensure the right network is being used, and the address is as intended. If tokens get sent to a random address there is no method or process for recovering them. There is no consumer protection in crypto!

What did we miss?

- Airdrops – because blockchain data is public new projects can easily view wallet addresses and send them tokens to increase visibility and achieve immediate wider token distribution. Famous airdrops include Stellar Lumens, Uniswap, and Ethereum Name Service.

- Tokenomics is the new blockchain branch of token distribution and incentives. It’s wise to view most projects as ‘experiments-in-progress’ and be cautious of marketing claims.

About the Author

Jeff is a Senior Lecturer in Blockchain & Cryptocurrencies at AUT and an Executive Council member of BlockchainNZ. He can be found tweeting about crypto at @japple.