Every time we swipe our bank card, upload a photo to Facebook, watch a video on YouTube, use a loyalty discount, hand over a prescription, read an article online, we’re giving ourselves away.

In 2018, a detailed, digital record of our lives is a valuable commodity. Companies, governments, and even charities can use what we reveal about ourselves to make money. But they can also use it to make our lives easier, our cities smarter, and our societies fairer. This new marketplace of information exists without any broadly agreed master plan, or rules.

TAKING OWNERSHIP OF OUR DIGITAL SELVES

Technologists are trying to take back the internet for the more than 3 billion people who use it. Giving people total control of their own digital data has been described as a ‘key task of this century’. But are we ready for that? Katie Kenny reports.

There’s a line of what looks like glitter on the floor. The line is 182 centimetres long and 1 millimeter wide, though stray sparkles blur its straight edge.

Luke Munn is also 182cm tall, and he made the line, in more ways than one. He posted the holiday photos, wrote the status updates and birthday wishes. The glitter is data; his entire Facebook history, downloaded onto CDs then shredded and arranged for this project, titled ‘Timeline’.

“It’s really about embodiment, taking something immaterial and making it material,” says Munn, from his home in Dairy Flat, north of Auckland. “I’m interested in the collapse between the virtual and real worlds.”

The Christchurch-born artist, whose works have been featured around the world — from Barcelona to London, New York to Istanbul — says he’s always been interested in contemporary technologies, and how they shape our everyday lives.

Eight years ago, he committed “Facebook suicide”. He was uncomfortable with the notion a Californian technology company was profiting off his social activity. He’s not the only one.

WHO OWNS YOU? /

The hard core programmers who helped build the web feared commercialisation. Of course, that was inevitable, and has allowed it to flourish as a platform for creativity and innovation. Things that you traditionally had to pay for (the news, for one) became freely available online.

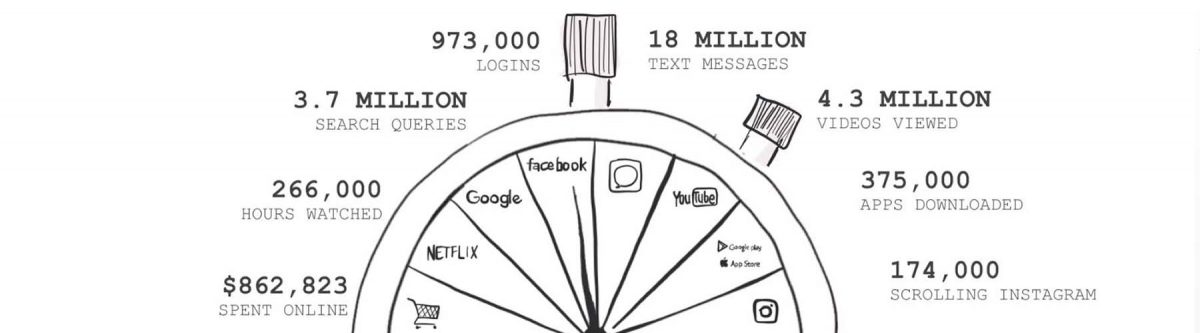

As the internet grew, so did the amount of data users generated. And we didn’t keep control of that data. Instead, our digital information became a kind of payment for free or cheap services. Hence the truism: “If you’re not paying for it, you’re not the customer; you’re the product being sold.” (Slate’s Will Oremuspenned perhaps a more accurate but ungainly alternative: “If you aren’t paying for it with money, you’re paying for it in other ways.”)

The big data business model was born; allowing advertisers to target us, companies to personalise pricing, government agencies to make predictions about us, and technology giants to train artificial intelligence systems (such as Google’s reported use of data from Android devices to help its algorithms predict our behaviours).

Our digital selves are now scattered across tens, or possibly hundreds, of different sites. For a long time, we’ve been OK with that. We’ve become comfortable with the idea that Facebook owns our social circle or Google owns our search history.

But as more intimate data, such as medical records (everything from medications to diagnoses to whether you’ve had an abortion), becomes digitised, a growing number of people are asking how we want it used, by governments, universities, and corporations, during our lifetime, and beyond.

Let’s focus on healthcare data, for a moment. Legally, a deceased person can’t have their privacy breached under New Zealand’s Privacy Act 1993. While the Health Information Privacy Code prevents disclosure of personal data for 20 years after death, there are few other barriers to the posthumous use of digitised healthcare information. This information has incredible potential to improve care, but also to be commercially exploited, says Dr Jon Cornwall, a senior lecturer at Otago Medical School’s Centre for Early Learning in Medicine, who’s researching the issue.

“Most people would be happy to donate their information for the benefit of everyone, but as soon as you attach financial value to that, you have problems.”

Giving away personal data with every online interaction can feel as inconsequential as scattering glitter, or shedding skin cells. It’s not until we take a step back and see what can be made of it, that we realise its true value. Cornwall says giving away sensitive data, such as, say, genomic information, is more akin to donating an organ.

“People can decide [whether or not] to donate their organs after death,” Cornwall says. “But, at the moment, people aren’t choosing to donate their data. They’re not given that option.”

But in one recent case, they were. And when given the chance to opt out, most didn’t.

In July this year, DNA testing service 23andMe, announced a new deal with pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). For $460m (US$300m), the drug giant gets access to 23andMe’s database. 23andMe said its five million-odd customers could opt out of their data being used for drug research, but the vast majority opted in — perhaps not appreciating they were essentially paying to donate their data to a huge company conducting a for-profit research project.

THE DATA POLICE /

What would happen if 23andMe lost control of its data? Or if GSK used it for some nefarious or distasteful purpose? Currently, a patchwork of insufficient regulations is all that’s keeping misuse in check. New laws such as Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) are lifting expectations of best practice. In response, companies around the world had to update their policies by May 28 this year to comply with the tough privacy rules, which include ‘the right to be forgotten’, or, the right to require a company to erase all of your personal data and halt third party processing of that data.

Many of the public submissions about the Privacy Bill introduced to Parliament this year, to repeal and replace the Privacy Act 1993, refer to the GDPR as exemplary. The key changes provided for by the bill are: giving more power to the Office of the Privacy Commission to issue compliance orders; introducing criminal offences with fines up to $10,000; and making it mandatory for organisations to report privacy breaches that “pose a risk of harm to people”.

However, the likes of the Privacy Commissioner and InternetNZ have said the bill doesn’t go far enough. It doesn’t, for example, include the right to be forgotten.

Technology itself is another line of defence. For many years, technologists have been working at ways to secure our digital personalities. Now that the issue has become a mainstream concern — and technology has sufficiently advanced — groups in New Zealand and around the world believe they’re on the cusp of so-called self-sovereign identity systems.

Tim Berners-Lee is leading the development of one of these systems at the world-renowned Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The world wide web founder this year wrote an open letter laying out his concerns about the concentration of power online, with “a new set of gatekeepers” controlling which ideas are seen and shared.

“What’s more, the fact that power is concentrated among so few companies has made it possible to weaponise the web at scale.”

Mark Pascall, of blockchainlabs.nz, shares concerns that cyberspace has become cyburbia — privately owned and operated.

Cryptocurrency and blockchain circles are typically populated by slick, self-described experts with bombastic presentations. Pascall stands out not only for his height but for his softly-spoken, unassuming manner. Like those early programmers, he believes in creating an accessible, safe and sustainable web.

“The world has moved into what many people would argue is a very dangerous place, where a handful of companies now own and control our personal information at an unprecedented scale in order to drive profit to their shareholders,” he says.

A decade ago, technology enthusiasts began buzzing about a new cryptocurrency called Bitcoin. This form of digital money, invented by a programmer, or programmers, named Satoshi Nakamoto, proved it was possible to exchange value online without an intermediary such as a bank. All Bitcoin transactions are registered, chronologically, in blocks of data. Those blocks of data are then linked to all previous blocks, and stored on hundreds of thousands of computers around the world that make up the network. The resulting record is called the blockchain.

This software architecture has been replicated and tweaked to store all kinds of data anonymously, yet securely. The data is distributed, meaning it isn’t stored in a central place, and it’s decentralised, meaning it’s not owned by a central agency. If you’re familiar with Google Sheets, this is kind of like an encrypted, read-only sheet.

“The blockchain gives some very powerful tools that we as developers, entrepreneurs, disruptors, can start to use to rethink privacy and how we control our data,” Pascall says.

If you believe the hype, blockchain is the future. But critics say the technology still has issues with efficiency, and scalability. There are few applications of it in the real world.

Pascall thinks the race to create identity systems is helping change that. “I feel people are genuinely becoming more nervous about the amount of control organisations like Facebook and Google now have over us,” he says. “We don’t have any better alternatives, currently, but I think we’ll see a shift that will change the face of commerce and society.”

ID ME /

Wynyard Quarter describes itself as Auckland’s newest waterfront neighbourhood. Formerly an industrial port, it’s now the site of high-end residential and commercial developments. It’s also the home of an organic movement known as Wynyard Innovation Neighbourhood; comprised of like-minded, non-competitive companies sharing knowledge and supporting local innovation.

Last year, ASB Bank, Datacom, Mercury, Spark Ventures and others started working on a digital identity platform, under the stewardship of the Department of Internal Affairs (DIA). Guy Kloss, then at Spark Ventures but now at software company SingleSource, was heavily involved in the project, called Kauri ID, from the beginning and now works on it full time.

So if all these big companies are involved, who owns the project? “Nobody really owns it,” Kloss says. “That’s the refreshing thing about it. If someone claims intellectual property on it, they’re dooming it to failure. Instead, it becomes an open protocol. Something that is basic, versatile, and it’s up to everyone else to build a business model around it.”

The vision is twofold: to give power back to individuals by allowing them to be in control of their digital identity, and to take the pain out of compliance for organisations and enable “risk free business”.

“We didn’t just use blockchain because it’s hip at the moment,” Kloss says. Rather, it allows Kauri ID to be secure, immutable, and free from custodianship. Unlike with Facebook, and Google, with Kauri ID the user is in control of their own information, and who has access to it. That’s what self-sovereign means.

A self-sovereign system gives users more control even than services such as RealMe, the verified login tool Kiwis can use to prove to businesses and government departments who they are without having to hand over physical documents such as passports. While the DIA initiative has been praised for its security practices, it still involves a third party looking after the data.

Kloss hopes Kauri ID will “permeate throughout our entire life” — that people will use it to become AA members, or get a bank loan, or join their local library, or buy beer, without having to go through a third party.

The idea is the user will create their own chain of identity “hooks”, he explains. Each hook represents a different part of their identity; one hook for social networks, one for finances, another for Work and Income, perhaps, another for the local library.

“Only the individual holds the encryption key. So their information could be painted on the Sky Tower in plain sight, and no one else would be any the wiser about whose it is and what it means.”

If you need to provide your name and date of birth to use a service, for example, you unhook only what’s needed. “If I go and buy alcohol, I usually present my driver’s license, which contains all kinds of information. In the end, the retailer only needs to know, not even my birthday, just that I’m over 18.”

Ideally, he adds, the technology could be used not just throughout the country but across the globe. But that’s a long way off. Kloss expects to have a working prototype ready for testing later this year, but says “mainstream” adoption could be a decade away.

“Hopefully within one or two years, there’ll be pockets of society using it, here and there.”

Kauri ID is just one of several similar projects in New Zealand. Others include Sphere Identity and Ego Identity. On its website, Sphere says it’ll be launching this year, but that doesn’t seem to have happened yet. (CEO Katherine Noall didn’t respond to my request for comment.)

Ego Identity is a startup born from Kiwibank’s FinTech Accelerator programme, and backed by Centrality, a Kiwi “blockchain venture studio”. (Centrality also has ties with Kauri ID.)

Andy Higgs, general manager of strategic partnerships at Centrality, describes self-sovereign identity as New Zealand’s next big innovation, “like Eftpos, 30 years ago”. Higgs’ vision — and Centrality’s — is of a peer-to-peer marketplace where consumers have control of their own data.

“Data has become controlled by a few rent-seeking, ‘middle men’. What we’re trying to do is decentralise the process and distribute that data back to people who are creating the value,” he says. “It all starts with digital identity, because you can’t create a peer-to-peer marketplace unless you can identify a person, or business, and that they’re connected to a wallet address, which is basically like a bank account in the blockchain world.” (No one has to trust anyone else because it’s impossible to cheat the system, provided the software has been written correctly.)

In this marketplace, data would be “tokenised”, meaning it would have value and individuals would get rewarded for sharing it. “It’s kind of like loyalty on steroids,” Higgs says. “You might be prepared to give away your facial data for skipping the queue at customs, for example.”

In order for this sort of thinking to truly take off, Higgs acknowledges the public has to be on board. “Working on the Ego Identity project, it’s all very cool, and we feel very noble, giving people their data back, but we have to keep asking, where’s the value for the customer? How do we make people care? Well, you’ve got to give them a better experience, you’ve got to make it easier, and potentially reward them on top of that.”

If this sounds a bit far-fetched that’s because, well, right now, it is. And it’s fair to say blockchain has a bit of PR problem to work through. Bitcoin introduced blockchain to the world, which attracted public interest and money, but also buzzwords and bandwagon behaviour.

But, at the very least, these movements might get people thinking about the value of their data. Even if it’s being held by someone else, Kiwis, under the Privacy Act, have the right to request information held about them, and correct it. Organisations also have an obligation to be transparent about how they’re using it.

“We’re at a point now where there’s a groundswell of opinion around the world that this data thing needs to be sorted out,” says Peter Fletcher-Dobson. “And at the root of it is this idea of self-sovereign identity.”

Fletcher-Dobson, until recently a digital advisor to Kiwibank, now runs his own innovation consultancy. He sees digital identity as being “one of the key tasks of this century”. “I think we’ll look back and see it as amazing that we didn’t have this capability, this right if you like, to own our own data. It’ll be like not having the right to vote.”

Article source: Stuff

Published under Creative Commons license.